1.

The Accountant’s P&L

Rambus designs and sells chips. Their kit goes into computer memory systems. Those chips help enable high-performance memory perform. Data centers demand the highest memory performance. That’s where the shop’s chips end up.

Rambus also earns royalties from memory makers — SK Hynix, Samsung and Micron. Rambus develops a lot of fundamental technologies related to memory. Memory makers pay Rambus to use this technology in their systems under long-term agreements.

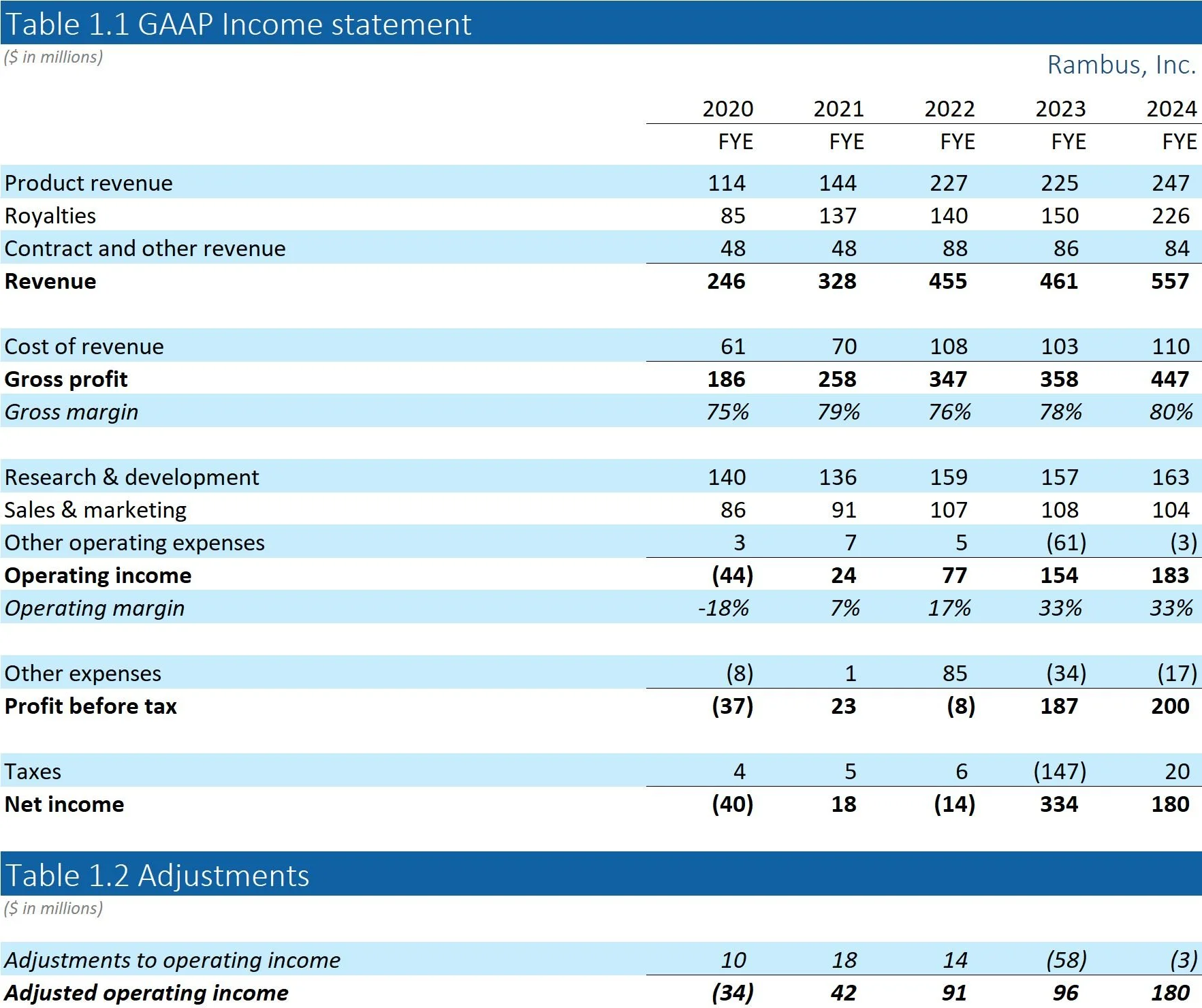

The shop’s financial performance has been great. Since 2020, it’s more than doubled revenue. Operating income went from negative $44m to $183m. Does that give investors an accurate picture of the company?

A few things jump out.

First, management makes a few recommendations to adjust operating income. Lamplighter gives credit for some of those adjustments. Table 1 does this.

Management adjust for things like transaction costs for acquisitions, restructurings and gains on the sale of divisions. These are things that are one-off expenses. On this tally, operating income went from negative $394m to $374m during the years Lamplighter looked at. Some bigger swings happened in individual years: 2022 and 2023.

Management would also like investors to adjust income for stock-based compensation. Lamplighter disagrees. It treats that in a separate section.Rambus doesn’t make the chips that it sells. It designs and markets them. Someone else — TSMC — does the making and bears all the costs of raw materials, gear and technicians to run that gear. Rambus doesn’t spend on machines and factories — traditional investments.

It runs a “capital lite” business. This is part of what enables its high margins. It does invest though. It pays engineers to develop new technologies and products that will show up in the marketplace sometime in the future.

Rambus lives in a part of the value chain for semiconductors that is “high value/hard to account for.”There’s a good deal of coordination between Rambus and its customers to work out what they need, what they’re willing to pay for and all the bells and whistles for each generation of memory. “Coordination” goes into research & development and sales & marketing expense. The payoff comes years later. This is an “investment” that Rambus makes.

Management throws another curveball. It prints a metric, “licensing billings,” in its earnings releases. It doesn’t incorporate this into its P&L or say much about it anymore. Is it useful to investors? How should they use it to frame the business’ economics?

The challenge in assessing Rambus, the investment, is to get a clear picture of its economics. An investor wants to match the company’s spending to the revenue that spendings enables. Lamplighter walks through how to treat R&D, sales & marketing, and stock-based compensation to do this. Then it works through the Licensing billings issue. The first step is research & development expenses.

2.

Research & Development

Rambus spends a lot on R&D. It shelled out $754m on R&D over the past five years, more than a third of its revenue. Accountants treat this like an expense. Rambus spends a dollar on R&D, a dollar of R&D shows up as an expense on its P&L.

Do those dollars spent on R&D in a year support those dollars of revenue in that same year?

Well, no. Accountants usually try to match expenses to revenue. If Rambus bought a machine that made chips and lasted five years, the accounting would have it run 20% of the cost through its P&L each year, matching its production.

R&D is squishier. Some R&D dollars go into dead ends. Other R&D dollars go into projects two-years out that end up being more like five years out. Accountants have a hard time matching a particular dollar of R&D to a particular dollar of revenue. So, they expense it all.

Memory R&D cycles are particularly long and uncertain. Most of R&D expenses don’t relate to revenues until years later. Rambus announced it had developed Serial Presence Detect and Temperature Sensors products back in 2022. Those are only just starting to ramp into customer production now, in 2025. Rambus spent most of the R&D dollars that went into those products before 2022. The revenue it will get from those products will mostly happen after 2025. Other products live on similar timelines.

Based on this framework, Lamplighter delayed running Rambus’ R&D expenses by three years. If it spent a dollar on R&D in 2021, that dollar would start to run through the P&L in 2024.

Memory generations last longer than a year. New products don’t hit the market at once. They ramp. Management has talked about Rambus’ SPD and temperature sensor beginning to contribute to revenue in 2025, but not being fully adopted by the ecosystem until late 2026. After that, those product will have some steady-state of sales for a few years. Lamplighter spread Rambus’ R&D spending over four years. We’ll call this the “Mauboussin Shuffle.”

Leading edge product introductions have contracted from two years to one. Why not use a shorter lifecycle?

Back when Rambus was just a royalty company, it spent between $100m and $140m on R&D. Most of its royalty business is under contract for 10 years. This structure supports matching R&D spend over that structure, 10 years.

Now that Rambus is a product company it’s increased it’s R&D spending to…actually it’s the same. It spends about the same now on R&D as it did when it was just a royalty company.

A couple of takeaways here. First: good job management. That’s solid expense control. They’ve built an entire second business without any observable overhead increase.

Second, the structure of their royalty business supports a longer amortization period than the four years that Lamplighter chose. The company spends to keep its patents fresh. This provides value under its long term royalty agreements. Its agreement with Micron lasts five years before it needs to renew. Its agreements with SK Hynix and Samsung last ten.

If half the R&D relates to this business, the other half would have to be expensed in the first year to get an amortization period of five years. That’s still longer than what Lamplighter chose for this analysis.

Lastly, building a product business that’s grown 30% per year over the past decade without increasing R&D points to an increasing return on R&D spending. Some of this has been riding trends outside the company’s direct control — the voracious data center build-out, the shift from the DDR4 generation to DDR5, where it has a much larger market share, and the rise of AI.

Several new products and markets offer Rambus the chance to keep up this pace. Its companion chip effort — SPD and temperature sensors — is part of this. Rambus also plans to ramp an MRDIMM product that it introduced at the end of 2024. It also has a client product program that would expand its potential beyond data centers to reach consumers too.

Some of these fronts won’t pan out. They don’t all have to for Rambus to keep-up its return on R&D.

3.

Sales & Marketing

Rambus has attended conferences at least every other week through the first half of 2025. The International Symposium on Computer Architecture and PCI-SIG DevCon and the rest are aimed squarely at the technical crowd. They serve to introduce new products and capabilities to the marketplace. Once out there, then the long process of integration begins.

Rambus introduced its MRDIMM product in late 2024. It would make a single sale until Intel launches its Diamond Rapids generation processors in 2026. Rambus has been pounding the pavement in the meantime to drum up customer adoption in anticipation of the launch.

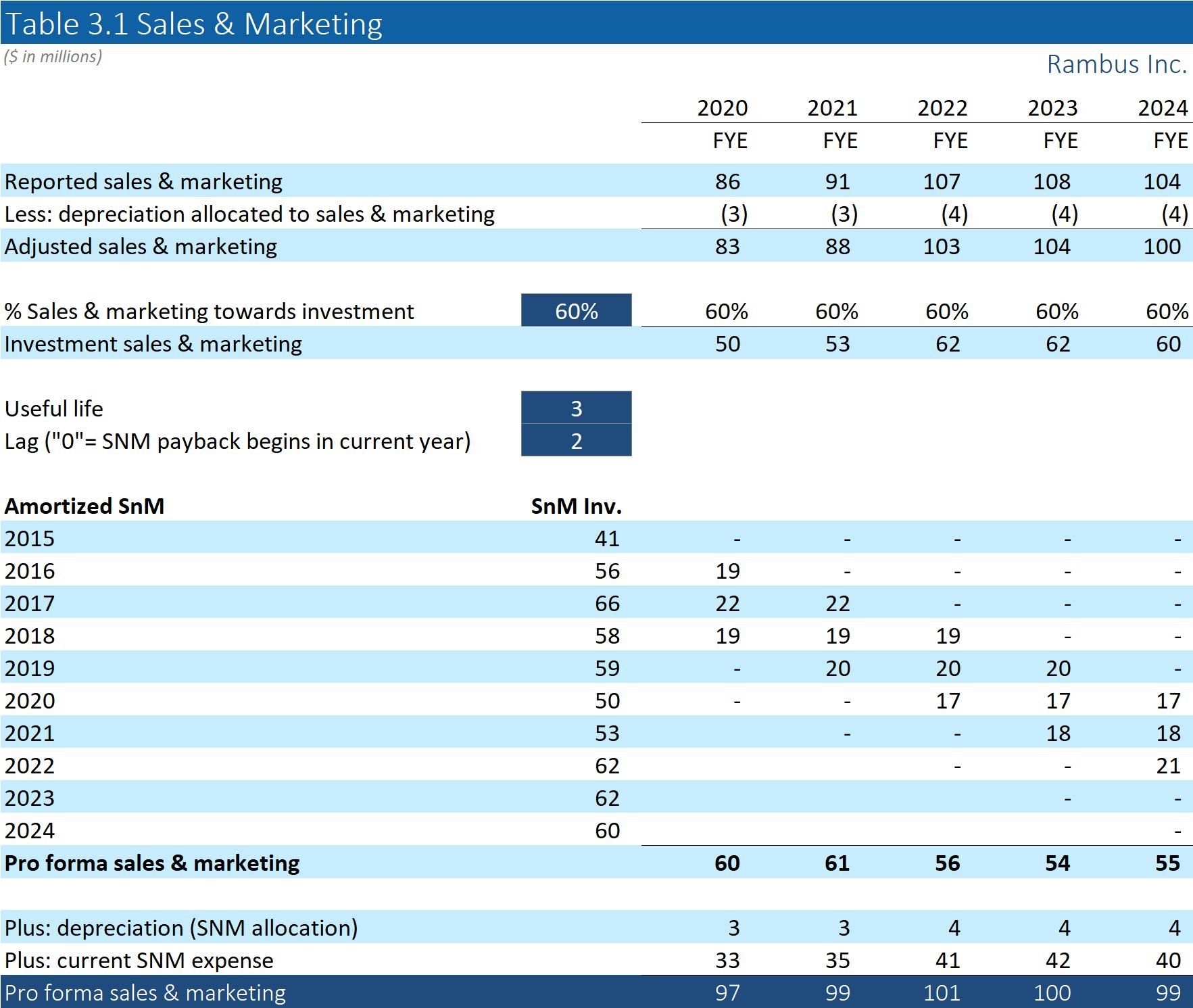

Like with R&D expenses, the revenue from Sales & Marketing activity won’t match the spending.

Some Sales & Marketing expense relate to current year revenue as staff take orders and ensure delivery. Lamplighter leaves 40% of Rambus’ Sales & Marketing expense alone.

The other 60% of Sales & Marketing expense, Lamplighter delays for two years, the lag implied by Rambus’ MRDIMM product. Some of its products have shown an even longer time-to-market, like its CXL solutions. Lamplighter spreads those delayed Sales & Marketing expenses over the following three years as support for the products continues over their lifecycle.

4.

Stock-based Compensation

There are two big ways to think about stock-based compensation. The first is as a way to raise money from investors. The investors also happen to be employees. Employees have great insight and incentive into a company’s prospects. If they’re really good, employees will be happy to get “paid” and invest that money right back into the company. For many Silicon Valley adventures, this is the right way to think about stock-based compensation.

Lamplighter’s made the case for this framework before, looking at Planet Labs.

The other way to think about compensation is that its just that: compensation. You pay your employees in stock rather than in cash, but that’s just semantics. It’s still just compensation.

This is the way to think about Rambus’ stock-based compensation. The case for this is simple: it’s how management behaves. Rambus execs typically get their SBC then sell those shares for cash. The compensation ends up being cash with an extra step.

In the case of Rambus, Lamplighter doesn’t adjust the PnL for stock-based compensation.

5.

Licensing billings

Rambus reports “Licensing billings” in a footnote in its earnings releases. It relates to the actual amount of billing it does under its long-term royalty agreements.

But it already reports royalty revenue. How is this helpful?

This is an accounting deep cut. It relates to a change all the way back in 2017. FASB began making companies report revenue under ASC 606. This led to more consistent revenue recognition among companies. The gist is that companies report revenue when a customer takes control of a product or service.

For Rambus, under its old royalty contracts, it could no longer recognize revenue. Customers still paid Rambus under the contracts. Those dollars just didn’t show up on the P&L.

This is why 2020 royalty revenue was $85m. Rambus reported Licensing Billings to help investors see what the economics of the business actually were. They mostly ignored it.

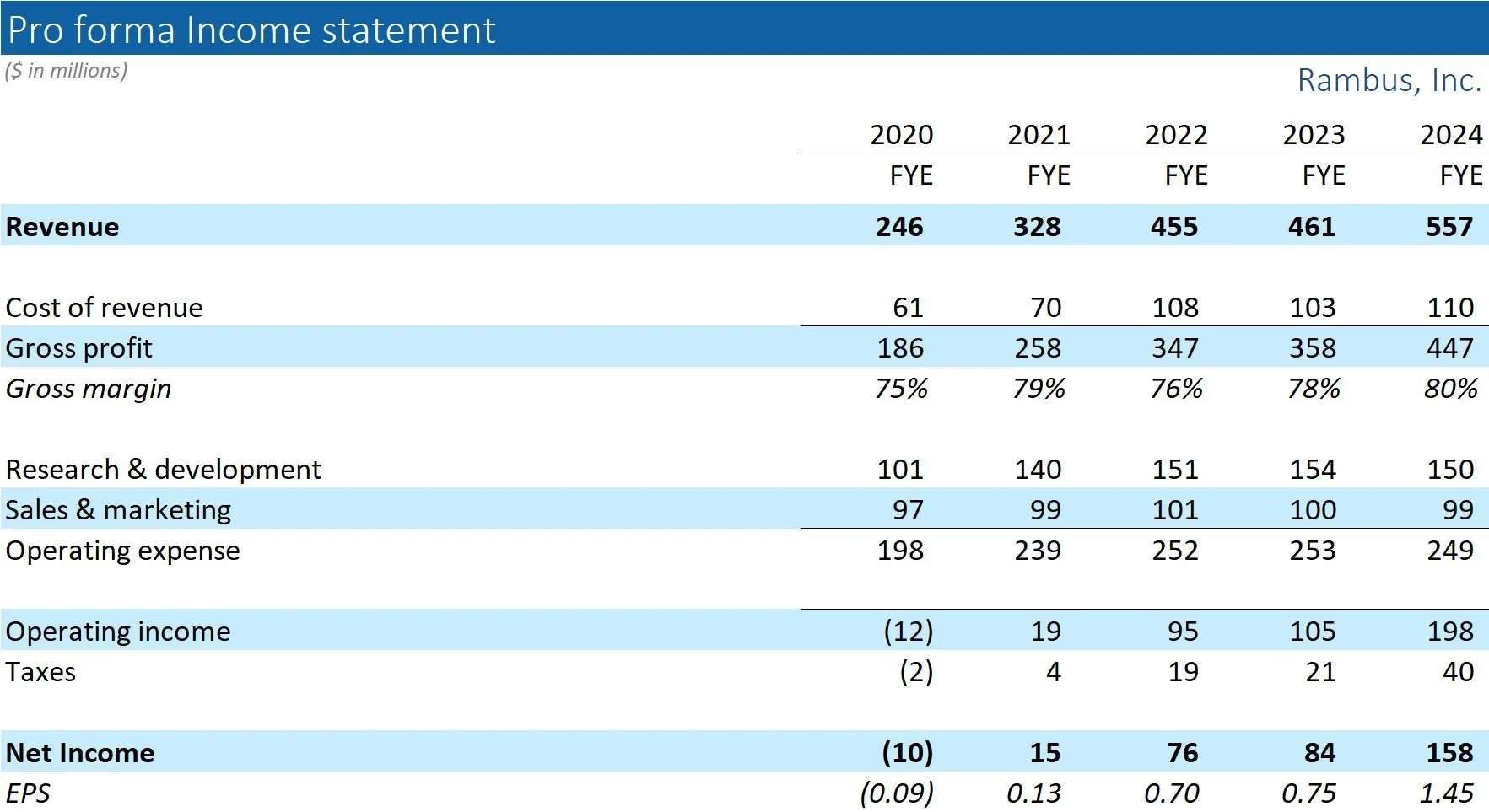

Table 5 adjusts Rambus’ P&L by replacing its reported royalty revenue with its Licensing Billings. This P&L includes Lamplighter’s changes to R&D and Sales & Marketing. It best reflects the state of the business.

Rambus’ royalty business stayed flat over this time. Topline and profit growth both fall to 9% per year.

Licensing billings and royalty revenue have converged in recent years. Rambus has replaced its old royalty contracts with new ones. Its lawyers drafted the new contracts so that it could report the incoming payments as revenue. This is what you’d expect from a business and reflects the economics.

6.

Profit?

Rambus has raked in $374m in operating profit over the past five years. That’s using GAAP. After our exercise adjusting R&D and sales & marketing? It jumps to $405, about 8% higher.

Disclaimer: None of this is investment advice. It's meant to illustrate ways LCM thinks about investing. Things that LCM decides are good investments for LCM and its clients are based on many criteria, not all of which are covered here. Some or all of LCM's ideas may not be suitable for other investors. LCM does not recommend investing either long or short any position mentioned. LCM may own positions in some of the companies mentioned. Some of its ideas will lose money — investing entails risk. See full disclaimer here.